This article is originally published at Toptal.

I had a programming interview recently, a phone-screen in which we used a collaborative text editor. I was asked to implement a certain API, and chose to do so in Python. Abstracting away the problem statement, let’s say I needed a class whose instances stored some data and some other_data. I took a deep breath and started typing. After a few lines, I had something like this:

class Service(object):

data = []

def __init__(self, other_data):

self.other_data = other_data

...

My interviewer stopped me:

- Interviewer: “That line:

data = []. I don’t think that’s valid Python?” - Me: “I’m pretty sure it is. It’s just setting a default value for the instance attribute.”

- Interviewer: “When does that code get executed?”

- Me: “I’m not really sure. I’ll just fix it up to avoid confusion.”

For reference, and to give you an idea of what I was going for, here’s how I amended the code:

class Service(object):

def __init__(self, other_data):

self.data = []

self.other_data = other_data

...

As it turns out, we were both wrong. The real answer lay in understanding the distinction between Python class attributes and Python instance attributes.

Note: if you have an expert handle on class attributes, you can skip ahead to use cases.

Python Class Attributes

My interviewer was wrong in that the above code is syntactically valid. I too was wrong in that it isn’t setting a “default value” for the instance attribute. Instead, it’s defining data as a class attribute with value []. In my experience, Python class attributes are a topic that many people know something about, but few understand completely.

Python Class Variable vs. Instance Variable: What’s the Difference?

A Python class attribute is an attribute of the class (circular, I know), rather than an attribute of an instance of a class. Let’s use a Python class example to illustrate the difference. Here, class_var is a class attribute, and i_var is an instance attribute:

class MyClass(object):

class_var = 1

def __init__(self, i_var):

self.i_var = i_var

Note that all instances of the class have access to class_var, and that it can also be accessed as a property of the class itself:

foo = MyClass(2)

bar = MyClass(3)

foo.class_var, foo.i_var

## 1, 2

bar.class_var, bar.i_var

## 1, 3

MyClass.class_var ## <— This is key

## 1

For Java or C++ programmers, the class attribute is similar—but not identical—to the static member. We’ll see how they differ later.

Class vs. Instance Namespaces

To understand what’s happening here, let’s talk briefly about Python namespaces. A namespace is a mapping from names to objects, with the property that there is zero relation between names in different namespaces. They’re usually implemented as Python dictionaries, although this is abstracted away. Depending on the context, you may need to access a namespace using dot syntax (e.g., object.name_from_objects_namespace) or as a local variable (e.g., object_from_namespace). As a concrete example:

class MyClass(object):

## No need for dot syntax

class_var = 1

def __init__(self, i_var):

self.i_var = i_var

## Need dot syntax as we've left scope of class namespace

MyClass.class_var

## 1

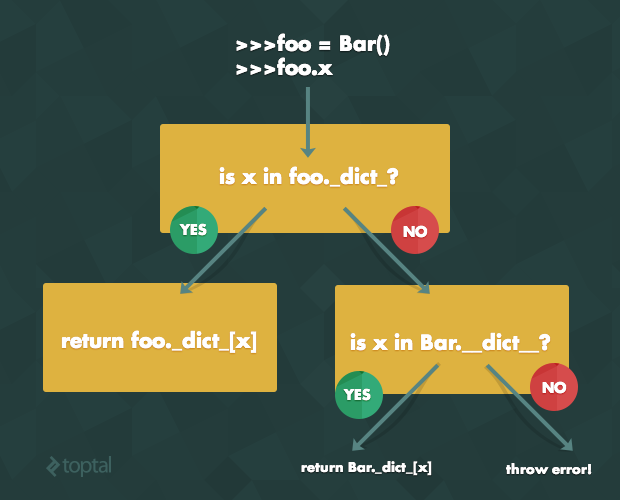

Python classes and instances of classes each have their own distinct namespaces represented by pre-defined attributes MyClass.__dict__ and instance_of_MyClass.__dict__, respectively. When you try to access an attribute from an instance of a class, it first looks at its instance namespace. If it finds the attribute, it returns the associated value. If not, it then looks in the class namespace and returns the attribute (if it’s present, throwing an error otherwise). For example:

foo = MyClass(2)

## Finds i_var in foo's instance namespace

foo.i_var

## 2

## Doesn't find class_var in instance namespace…

## So look's in class namespace (MyClass.__dict__)

foo.class_var

## 1

The instance namespace takes supremacy over the class namespace: if there is an attribute with the same name in both, the instance namespace will be checked first and its value returned. Here’s a simplified version of the code (source) for attribute lookup:

def instlookup(inst, name):

## simplified algorithm...

if inst.__dict__.has_key(name):

return inst.__dict__[name]

else:

return inst.__class__.__dict__[name]

And, in visual form:

How Class Attributes Handle Assignment

With this in mind, we can make sense of how Python class attributes handle assignment:

- If a class attribute is set by accessing the class, it will override the value for all instances. For example:

foo = MyClass(2) foo.class_var ## 1 MyClass.class_var = 2 foo.class_var ## 2At the namespace level… we’re setting

MyClass.__dict__['class_var'] = 2. (Note: this isn’t the exact code(which would besetattr(MyClass, 'class_var', 2)) as__dict__returns a dictproxy, an immutable wrapper that prevents direct assignment, but it helps for demonstration’s sake). Then, when we accessfoo.class_var,class_varhas a new value in the class namespace and thus 2 is returned. - If a Paython class variable is set by accessing an instance, it will override the value only for that instance. This essentially overrides the class variable and turns it into an instance variable available, intuitively, only for that instance. For example:

foo = MyClass(2) foo.class_var ## 1 foo.class_var = 2 foo.class_var ## 2 MyClass.class_var ## 1At the namespace level… we’re adding the

class_varattribute tofoo.__dict__, so when we lookupfoo.class_var, we return 2. Meanwhile, other instances ofMyClasswill not haveclass_varin their instance namespaces, so they continue to findclass_varinMyClass.__dict__and thus return 1.

Mutability

Quiz question: What if your class attribute has a mutable type? You can manipulate (mutilate?) the class attribute by accessing it through a particular instance and, in turn, end up manipulating the referenced object that all instances are accessing (as pointed out by Timothy Wiseman). This is best demonstrated by example. Let’s go back to the Service I defined earlier and see how my use of a class variable could have led to problems down the road.

class Service(object):

data = []

def __init__(self, other_data):

self.other_data = other_data

...

My goal was to have the empty list ([]) as the default value for data, and for each instance of Service to have its own data that would be altered over time on an instance-by-instance basis. But in this case, we get the following behavior (recall that Service takes some argument other_data, which is arbitrary in this example):

s1 = Service(['a', 'b'])

s2 = Service(['c', 'd'])

s1.data.append(1)

s1.data

## [1]

s2.data

## [1]

s2.data.append(2)

s1.data

## [1, 2]

s2.data

## [1, 2]

This is no good—altering the class variable via one instance alters it for all the others! At the namespace level… all instances of Service are accessing and modifying the same list in Service.__dict__ without making their own data attributes in their instance namespaces. We could get around this using assignment; that is, instead of exploiting the list’s mutability, we could assign our Service objects to have their own lists, as follows:

s1 = Service(['a', 'b'])

s2 = Service(['c', 'd'])

s1.data = [1]

s2.data = [2]

s1.data

## [1]

s2.data

## [2]

In this case, we’re adding s1.__dict__['data'] = [1], so the original Service.__dict__['data'] remains unchanged. Unfortunately, this requires that Service users have intimate knowledge of its variables, and is certainly prone to mistakes. In a sense, we’d be addressing the symptoms rather than the cause. We’d prefer something that was correct by construction. My personal solution: if you’re just using a class variable to assign a default value to a would-be Python instance variable, don’t use mutable values. In this case, every instance of Service was going to override Service.data with its own instance attribute eventually, so using an empty list as the default led to a tiny bug that was easily overlooked. Instead of the above, we could’ve either:

- Stuck to instance attributes entirely, as demonstrated in the introduction.

- Avoided using the empty list (a mutable value) as our “default”:

class Service(object): data = None def __init__(self, other_data): self.other_data = other_data ...Of course, we’d have to handle the

Nonecase appropriately, but that’s a small price to pay.

So When Should you Use Python Class Attributes?

Class attributes are tricky, but let’s look at a few cases when they would come in handy:

- Storing constants. As class attributes can be accessed as attributes of the class itself, it’s often nice to use them for storing Class-wide, Class-specific constants. For example:

class Circle(object): pi = 3.14159 def __init__(self, radius): self.radius = radius def area(self): return Circle.pi * self.radius * self.radius Circle.pi ## 3.14159 c = Circle(10) c.pi ## 3.14159 c.area() ## 314.159 - Defining default values. As a trivial example, we might create a bounded list (i.e., a list that can only hold a certain number of elements or fewer) and choose to have a default cap of 10 items:

class MyClass(object): limit = 10 def __init__(self): self.data = [] def item(self, i): return self.data[i] def add(self, e): if len(self.data) >= self.limit: raise Exception("Too many elements") self.data.append(e) MyClass.limit ## 10We could then create instances with their own specific limits, too, by assigning to the instance’s

limitattribute.foo = MyClass() foo.limit = 50 ## foo can now hold 50 elements—other instances can hold 10This only makes sense if you will want your typical instance of

MyClassto hold just 10 elements or fewer—if you’re giving all of your instances different limits, thenlimitshould be an instance variable. (Remember, though: take care when using mutable values as your defaults.) - Tracking all data across all instances of a given class. This is sort of specific, but I could see a scenario in which you might want to access a piece of data related to every existing instance of a given class. To make the scenario more concrete, let’s say we have a

Personclass, and every person has aname. We want to keep track of all the names that have been used. One approach might be to iterate over the garbage collector’s list of objects, but it’s simpler to use class variables. Note that, in this case,nameswill only be accessed as a class variable, so the mutable default is acceptable.class Person(object): all_names = [] def __init__(self, name): self.name = name Person.all_names.append(name) joe = Person('Joe') bob = Person('Bob') print Person.all_names ## ['Joe', 'Bob']We could even use this design pattern to track all existing instances of a given class, rather than just some associated data.

class Person(object): all_people = [] def __init__(self, name): self.name = name Person.all_people.append(self) joe = Person('Joe') bob = Person('Bob') print Person.all_people ## [<__main__.Person object at 0x10e428c50>, <__main__.Person object at 0x10e428c90>] - Performance (sort of… see below).

Under-the-hood

Note: If you’re worrying about performance at this level, you might not want to be use Python in the first place, as the differences will be on the order of tenths of a millisecond—but it’s still fun to poke around a bit, and helps for illustration’s sake. Recall that a class’s namespace is created and filled in at the time of the class’s definition. That means that we do just one assignment—ever—for a given class variable, while instance variables must be assigned every time a new instance is created. Let’s take an example.

def called_class():

print "Class assignment"

return 2

class Bar(object):

y = called_class()

def __init__(self, x):

self.x = x

## "Class assignment"

def called_instance():

print "Instance assignment"

return 2

class Foo(object):

def __init__(self, x):

self.y = called_instance()

self.x = x

Bar(1)

Bar(2)

Foo(1)

## "Instance assignment"

Foo(2)

## "Instance assignment"

We assign to Bar.y just once, but instance_of_Foo.y on every call to __init__. As further evidence, let’s use the Python disassembler:

import dis

class Bar(object):

y = 2

def __init__(self, x):

self.x = x

class Foo(object):

def __init__(self, x):

self.y = 2

self.x = x

dis.dis(Bar)

## Disassembly of __init__:

## 7 0 LOAD_FAST 1 (x)

## 3 LOAD_FAST 0 (self)

## 6 STORE_ATTR 0 (x)

## 9 LOAD_CONST 0 (None)

## 12 RETURN_VALUE

dis.dis(Foo)

## Disassembly of __init__:

## 11 0 LOAD_CONST 1 (2)

## 3 LOAD_FAST 0 (self)

## 6 STORE_ATTR 0 (y)

## 12 9 LOAD_FAST 1 (x)

## 12 LOAD_FAST 0 (self)

## 15 STORE_ATTR 1 (x)

## 18 LOAD_CONST 0 (None)

## 21 RETURN_VALUE

When we look at the byte code, it’s again obvious that Foo.__init__ has to do two assignments, while Bar.__init__ does just one. In practice, what does this gain really look like? I’ll be the first to admit that timing tests are highly dependent on often uncontrollable factors and the differences between them are often hard to explain accurately. However, I think these small snippets (run with the Python timeit module) help to illustrate the differences between class and instance variables, so I’ve included them anyway. Note: I’m on a MacBook Pro with OS X 10.8.5 and Python 2.7.2.

Initialization

10000000 calls to `Bar(2)`: 4.940s

10000000 calls to `Foo(2)`: 6.043s

The initializations of Bar are faster by over a second, so the difference here does appear to be statistically significant. So why is this the case? One speculative explanation: we do two assignments in Foo.__init__, but just one in Bar.__init__.

Assignment

10000000 calls to `Bar(2).y = 15`: 6.232s

10000000 calls to `Foo(2).y = 15`: 6.855s

10000000 `Bar` assignments: 6.232s - 4.940s = 1.292s

10000000 `Foo` assignments: 6.855s - 6.043s = 0.812s

Note: There’s no way to re-run your setup code on each trial with timeit, so we have to reinitialize our variable on our trial. The second line of times represents the above times with the previously calculated initialization times deducted. From the above, it looks like Foo only takes about 60% as long as Bar to handle assignments. Why is this the case? One speculative explanation: when we assign to Bar(2).y, we first look in the instance namespace (Bar(2).__dict__[y]), fail to find y, and then look in the class namespace (Bar.__dict__[y]), then making the proper assignment. When we assign to Foo(2).y, we do half as many lookups, as we immediately assign to the instance namespace (Foo(2).__dict__[y]). In summary, though these performance gains won’t matter in reality, these tests are interesting at the conceptual level. If anything, I hope these differences help illustrate the mechanical distinctions between class and instance variables.

In Conclusion

Class attributes seem to be underused in Python; a lot of programmers have different impressions of how they work and why they might be helpful. My take: Python class variables have their place within the school of good code. When used with care, they can simplify things and improve readability. But when carelessly thrown into a given class, they’re sure to trip you up.

Appendix: Private Instance Variables

One thing I wanted to include but didn’t have a natural entrance point… Python doesn’t have private variables so-to-speak, but another interesting relationship between class and instance naming comes with name mangling. In the Python style guide, it’s said that pseudo-private variables should be prefixed with a double underscore: ‘__’. This is not only a sign to others that your variable is meant to be treated privately, but also a way to prevent access to it, of sorts. Here’s what I mean:

class Bar(object):

def __init__(self):

self.__zap = 1

a = Bar()

a.__zap

## Traceback (most recent call last):

## File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

## AttributeError: 'Bar' object has no attribute '__baz'

## Hmm. So what's in the namespace?

a.__dict__

{'_Bar__zap': 1}

a._Bar__zap

## 1

Look at that: the instance attribute __zap is automatically prefixed with the class name to yield _Bar__zap. While still settable and gettable using a._Bar__zap, this name mangling is a means of creating a ‘private’ variable as it prevents you and others from accessing it by accident or through ignorance. Edit: as Pedro Werneck kindly pointed out, this behavior is largely intended to help out with subclassing. In the PEP 8 style guide, they see it as serving two purposes: (1) preventing subclasses from accessing certain attributes, and (2) preventing namespace clashes in these subclasses. While useful, variable mangling shouldn’t be seen as an invitation to write code with an assumed public-private distinction, such as is present in Java.

Latest posts by Michelle Young (see all)

- Styled-Components: CSS-in-JS Library for the Modern Web - May 29, 2018

- Intro to Python Image Processing in Computational Photography - May 23, 2018

- Python Class Attributes: An Overly Thorough Guide - May 16, 2018